By Miriam Adeney

In Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley in March 2018, I met a woman named Zaide. She is a Syrian refugee, with five children ranging in age from 21 to 3. Her husband was disabled in an accident in Saudi Arabia, where he lost an eye and the use of one leg. When their home in Aleppo was destroyed, the family fled to Lebanon. Now they live in a former chicken shed. Zaide digs potatoes to support the family during the season when there are potatoes.

She also attends the local Baptist church, wearing her hijab. The church has helped her with food and other needs. In this congregation, regular attendees are placed into small groups. Zaide’s group leader challenges the participants to memorize Bible verses.

“And I do!” she told me.

“What verses have you learned?” I wondered.

“Your word I have hid in my heart, that I might not sin against You—Psalm 119,” she said, and her face broke out in a smile. Then she continued without a pause, “Thanks be to God who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ!—1 Corinthians 15.” Leaning forward, she explained, “Jesus died for us. Jesus died for everybody. The cross is the center of everything. I want to learn as much as I can so I can take it all back when I return to Syria.”

What missiological categories fit Zaide? If “every man is an exception,” as Kierkegaard wrote, certainly every Muslim woman is an exception. Zaide is an ordinary Syrian woman faced with big challenges. Though not overly spiritual, she has spiritual longings. Thanks be to God, these are being met by Jesus and his people.

Four thousand years ago, God encountered another woman in the desert not too far from where Zaide lives. “Where have you come from, and where are you going?” God asked. God called Hagar by name. She marveled, “God, you see me.” Later, when her son was dying of thirst, God’s angel called to her, “Lift up your eyes and look! What do you see?” Hagar focused her vision and saw a well of water. They drank, and lived, and prospered.

There are many women who thirst for living water, like Hagar, like Zaide. Over the centuries, motivated by the love of Jesus, women have been pouring out this life-giving resource for their Muslim sisters.

Strangers and Friends

In the 1880s, the gently-educated Lilias Trotter traveled from Britain to Algeria where she invested the rest of her life. She witnessed to women and men, nurtured new believers, and wrote, illustrated, and distributed Christian publications. She traveled deep into the desert, where she found spiritually hungry people. She cried with those who suffered and even with those who apostasized. She loved Algeria, its people, its cultures, and its natural setting. As an artist, she decorated her manuscripts with sketches of the faces and flowers of the desert. She filled her journals with sunsets, rock formations, oases, questions and testimonies of men and women, and promises of God. With Abraham, she cried out, “Oh that Ishmael might live before Thee!”

Men and women were blessed by her ministry. In the Sahara Desert at the turn of the twentieth century, where “the men pleaded for books,” Lilias said, “I don’t know anything like the joy of reading with these men and seeing them begin to understand” (St. John, 1990, passim). Today there may be more than 150,000 Muslim-background Christians in the land where Lilias created and distributed books.

Lilias was part of the great women’s mission movement of the nineteenth century. Long before there were antibiotics and jet travel and diplomatic immunity, women were traversing jungles, deserts, and mountain ranges to enter the segregated and sequestered harems in many countries in order to bring good news to the women inside. During the “great century of missions,” American women “stitched together a missiology of local auxiliaries, sacrificial pennies, and ecumenical flexibility that blanketed the continent” (Robert 1996). By 1910, these women were administering and financing over forty distinct women’s mission agencies which supported more than 2,500 women missionaries, 6,000 indigenous Bible women, 3,263 schools, 80 hospitals, 11 colleges, and innumerable orphanages and dispensaries.

Blessing Her Own People

Some Muslims who come to Christ are persecuted. Some must keep their faith hidden. But others can be missionaries right in their own neighborhoods. Renda worked as a maid in an Indonesian Christian home. Here she was taught some of the parables of Jesus, and lovely songs. Most impressive was the love that Renda glimpsed. The husband and wife in this house showed real love to each other. “This is what marriage should be,” Renda whispered to herself.

The family’s love encompassed Renda too. She was unusual in that she could read Arabic, having had six years of religious school. Yet she could not read in her own Indonesian language. When the father of the family noticed this, he taught her to read, using Sunday school materials as curriculum. It was the stories, the songs, and the love that brought Renda to faith in Jesus. As she grew, she became known for her helpfulness and her singing.

Eventually Renda decided to return back home to live in the village where she had been born, a completely Muslim community. There she began to tell the children stories about Jesus. They excitedly repeated the stories to their parents. Some adults were drawn to Christ, while others were furious. The local Muslim religious leader reproved Renda. But because her uncle was the headman, family loyalty took precedence. Her uncle backed Renda’s right to witness graciously about the prophet Jesus. Today there is a 1000-square meter church in that village, bursting its seams, as a result of the witness of this Muslim-background maidservant.

Muslim Women’s Spirituality

Who are the thirsty women to whom Christians offer living water? Like human beings everywhere, most Muslim women don’t spend a lot of time thinking about God. They think about their duties. They think about the people with whom they are in close relationships—family, friends, neighbors, workmates, fellow members of women’s solidarity groups. They think about coming events, and the fun and pleasure that may ensue. They think about professional and business concerns. They worry about dangers and disasters. Religiously, they oscillate between conventional affirmation of beliefs and performance of rituals, and spurts of intense pursuit of the supernatural when they are in trouble. A minority study doctrine seriously.

Generally, women’s religion includes holistic and relational dimensions. Because most women bear children, cultures orient women toward some degree of competency in domestic and relational skills. Though childrearing occupies only a certain period of a mother’s life and some women do not bear children at all, nevertheless this motherly potential affects societies’ general expectations for women. Nurturance, vulnerability, interdependence, multitasking, and storytelling are characteristics that may develop in such contexts. Women’s religion, then, is not primarily cerebral, theoretical, or abstract. It must apply to the cries and celebrations and hungers and pains and betrayals and successes of the people with whom they live.

Still, Muslim women earnestly desire to live in a moral and godly society. A Gallup poll surveying 22 countries, covering 90% of the world’s Muslim women, underlines this assertion (Abdo and McGahed 2006). Even though the women who were polled deplored some of the restrictions of Sharia law, still the majority preferred to live under Sharia, because their crucial priority was to live in a moral and godly society. The benefits outweighed the detriments, they felt. Muslim women’s religion is not just instrumental—gaining answers to prayers—but endows them with honor and dignity as creatures of God, accountable to make choices that honor God, khalifas like Siti Hawa (Eve) who shared with Adam the responsibility to take care of God’s world.

Whether their knowledge and practice is superficial, or heavily spiritist, or serious and studied, Muslim women are spiritual beings. They want to live in a godly context. Their orientation is holistic, attentive to the concerns of people around them. They feel a need to tap into supernatural power from time to time. They long to pray with some confidence that they are being heard. They desire their dreams to be taken seriously. They love to hear and recite beautiful Scripture, and to do that in community with other women. In poor communities, they value microloans or any compassionate activities that will help them feed their children with dignity, and procure schooling for them. Certainly, there are challenges and difficulties in communicating the gospel to Muslim women. Yet we take encouragement from the words recited by our Syrian sister: “Thanks be to God who give us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.”

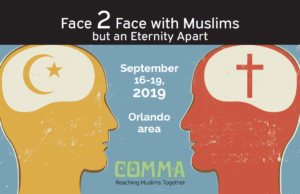

I will explore in more depth the idea of women’s contribution in reaching Muslims at the COMMA 2019 consultation September 16-19 in Orlando, FL. I hope to see you there. Invite a friend to this strategic and refreshing consultation and register at http://commanetwork/2019-consultation.com.

1.Patricia St.John. Until the Day Breaks: The Life and Work of Lilias Trotter. OM Publishing (UK), 1990.

2.Dana Robert, American Women in Mission: A Social History of their Thought and Practice Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1996, p. 137.

3.Abdo, Geneve and Dalia Mogahed. “What Muslim Women Want,” Wall Street Journal, December 13, 2006, p. A18.